Origin of IkebanaAsuka Period – Nanbokucho Period

In Japan different seasonal flowers bloom throughout the year. “Flowers to be appreciated,” “Yorishiro (an object that divine spirits are summoned to),” “Flower offerings on the Buddhist altar” --- with these interacting elements in place ikebana began to be formalized.

Flowers to be appreciated

Viewing plants and appreciating flowers are customs common in countries around the world. Since there are four distinct seasons in Japan, one can enjoy beautiful flowers throughout the year. In these circumstances people refined their sensibility for appreciating flowers. Anthologies of waka poetry such as the “Manyoshu” and “Kokinwakashu” included many poems on the topic of flowers.

Cherry tree at the Rokkakudo Temple

Since the Heian period, the word “flower” has become synonymous with cherry blossoms. The custom of flower viewing (cherry blossom viewing) has been practiced for centuries and is still enjoyed today.

Yorishiro (an object that divine spirits are summoned to)

Having lived in harmony with nature and sensed life’s fleetingness in the change of seasons, people found special meaning in evergreen trees. They believed that these trees are Yorishiro to which divine spirits are summoned. Kadomatsu, a pair of pine boughs used even today as decoration for the New Year, is one of the forms of Yorishiro.

Flower offering on the Buddhist altar

With the introduction of Buddhism to Japan in the 6th century, the custom of offering flowers on the Buddhist altar became common. As indicated by the use of the Chinese character meaning “flower” is the names of sutras such as the “Kegon-kyo (Avatamsaka Sutra)” and “Hokke-kyo (Lotus Sutra),” from the beginning flowers have been deeply related to Buddhism. Lotus is widely found in India where Buddhism originated, and it is a representative flower for Buddhist offerings. In Japan, however, other suitable flowers for each season were selected for this purpose. Among various ways of Buddhist offering, placing Mitsugusoku, a set of three ceremonial objects - flower vase, incense burner and candle holder – became popular in the Kamarura and Nanbokucho periods.

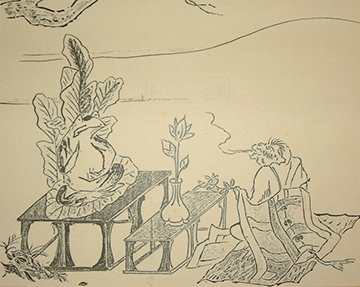

“Choju Jinbutsu Giga (Scroll of frolicking animals and humans)” Original scroll is owned by Kozanji temple, Kyoto

Buddhist floral offering is illustrated on this scroll from the Heian period. Lotus is offered in front of a frog mimicking Buddha.

Development of IkebanaEarly Muromachi Period

Ikebana developed during the process of experimenting with new approaches and techniques for placing flowers in Chinese vases. In Kyoto flowers arranged by Senkei Ikenobo of the Rokkakudo temple were widely praised.

Zashiki kazari and Tatehana

With the introduction of many Chinese paintings and containers to Japan, shoin-zukuri was developed as an architectural style suitable for display of these art objects. Oshiita, precursor to the tokonoma (alcove) and chigaidana (bi-level shelves) were set up in Buddhist temples and the residences of influential people including the Ashikaga family of the Muromachi Shogunate, and flower vases were displayed in these spaces. This style of decoration, called “zashiki kazari,” was refined by the Doboshu, attendants to the shogun. Flowers in a vase, incense in a burner, and candles lit in holders were placed as mitsugusoku (a set of three ceremonial objects). Tatehana (a formal flower arrangement with upright form) composed of shin (motoki) and shitakusa was arranged for this purpose.

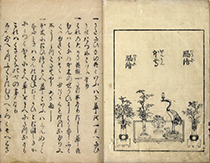

“Sendensho”

An old printed document from the early Edo Period, believed to contain ikebana teaching of the Muromachi Period. A drawing of flowers arranged as part of mitsugusoku (a set of three ceremonial objects) is included.

Senkei Ikenobo

In “Hekizan nichiroku,” the diary of a zen monk at Tofukuji temple, it is stated that in 1462 Senkei Ikenobo, a priest at the Rokkakudo temple, was invited by a warrior to arrange flowers, and that these flowers were highly praised by the people of Kyoto. The flowers created for zashiki kazari and the flowers arranged by Senkei Ikenobo went beyond yorishiro and traditional styles of Buddhist floral offering, and it can be said that the development of ikebana, unique to Japanese culture, took place at this time.

Oldest Extant Kadensho

“Kao irai no Kadensho” is believed to be the oldest extant manuscript of ikebana teaching, dating from a time shortly after that of Senkei Ikenobo. It shows various arranging styles of ikebana such as tatehana, kakebana (hung on a tokonoma post or wall) and tsuribana (hanging arrangements), enabling us to understand how ikebana was integrated into people’s lives.

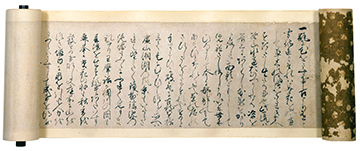

“Kao Irai no Kadensho”

This is believed to be the oldest extant manuscript of ikebana teachings handed down in Ikenobo. Dates from 1486 to 1499 are recorded at the end of the document.

Establishment of the Philosophy of IkebanaLate Muromachi Period

Senno Ikenobo, active as a master of ikebana, established a theory of ikebana teaching including not only technique but also philosophy, and a manuscript of his teachings was passed on to later generations.

Ikenobo Senno Kuden

The Muromachi shogunate was weakened during the Onin-Bunmei War which had devastated Kyoto, and the Doboshu’s zashiki kazari arrangements began to be assimilated by Ikenobo. In the first half of the 16th century Senno Ikenobo was praised as a “master of ikebana” for his arrangements at the Imperial Court and Buddhist temples. He compiled a theory of ikebana based on teachings since the time of Senkei Ikenobo, and he passed on a document called kadensho to his disciples. This kadensho, generally known as “Ikenobo Senno Kuden” mentions that in Ikenobo there is not only the mere act of appreciating beautiful flowers. For plants arranged in a vase it is important to observe their inner essence and express their natural form. In some cases even the use of a dry branch is valued. Yasunari Kawabata, in his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize for literature titled “Japan, the Beautiful and Myself,” introduced this philosophy and it became known worldwide.

Ikenobo Senno Kuden

Among several copies, this is the version that was handed down in 1537. It describes the philosophy and techniques of ikebana.

Establishment of Rikka’s Basic Form

The Ikenobo Senno Kuden explained the ideal form of shin and shitakusa in tatehana, but inclination toward a more complex arranging style is also apparent. In the kadensho by Sen’ei Ikenobo, successor of Senno Ikenobo, this inclination became clear, and a drawing in skeletal form of a style composed of seven yakueda (main parts or branches) was included. This style later began to be called “rikka.”

Tateru hana and Ikeru hana

Sen’ei Ikenobo was interested not only in tateru hana (composed in standing or upright style) but also in ikeru hana, arrangements that were lighter in feeling, and he stated that expressing the unique character of plants is essential. In addition to ikebana, the tea ceremony was also popular at this time, and Sen’ei Ikenobo seems to have had a strong awareness of flowers arranged for the tea ceremony.

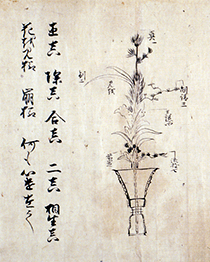

Ikenobo Sen’ei Kadensho

This manuscript was handed down in 1545. While passing on Senno Ikenobo’s philosophy of ikebana, it is noteworthy that this document shows the basic structure of rikka.

Refinement of RikkaAzuchi Momoyama period – Early Edo period

Senko Ikenobo II refined a style called rikka, in which the beauty of a natural landscape is expressed. He was often invited to the Imperial Court or to warrior’s residences, firmly establishing Ikenobo’s position in these societies.

Large Sunanomono Rikka at the Maeda Residence

In the Azuchi Momoyama Period Hideyoshi Toyotomi completed the unification of the country. Large tokonoma spaces began to be included in castles and warrior’s residences, and Ikenobo was asked to create large flower arrangements to be displayed in these spaces. A large sunanomono rikka arranged by Senko Ikenobo I in 1594 for the visit of Hideyoshi Toyotomi to the residence of Toshiie Maeda is said to have been praised as “the greatest Ikenobo work of an age.” A flower exhibition at Daiunin in Kyoto in 1599 by 100 disciples of Senko Ikenobo I attracted many viewers.

Large Sunanomono Rikka at Maeda ResidencePhoto: Naotatsu Kimura

Reproduction (2012) of a large sunanomono rikka, believed to have originally been created by Senko Ikenobo I in 1594 at the Maeda Residence. The name sunanomono derives from small white pebbles (suna in Japanese) spread on the surface at the base of the arrangement. Seen from the front, it is said that monkeys drawn on hanging scrolls displayed behind the arrangement looked as if they were playing on the arrangement’s pine branches.

Success of Rikka Gatherings at the Imperial Court

Senko Ikenobo II, successor to Senko Ikenobo I, created rikka at warrior’s residences, continuing to receive requests from warriors even after Ieyasu Tokugawa founded the Edo shogunate. In Kyoto Emperor Gomizuno-o often organized rikka gatherings with princes, aristocrats and monks, and Senko Ikenobo II played an active role as instructor on these occasions. Emperor Gomizuno-o retired in 1629 during the height of these rikka gatherings. Rikka gatherings were subsequently held at the Sento Imperial Palace.

Beginning of the Tanabata Gathering

Having been refined by Senko Ikenobo II, rikka was gradually appreciated not only by monks, aristocrats and warriors but also by townspeople. Ikenobo had leading pupils such as Daijuin Ishin, Takada Anryubo Shugyoku and Taemon Juichiya, and the number of Ikenobo disciples increased. Following rikka gatherings at the Imperial Court and Sento Imperial Palace, the Tanabata rikka gathering began to be held at the Rokkakudo temple, and this gathering became a popular annual event in Kyoto.

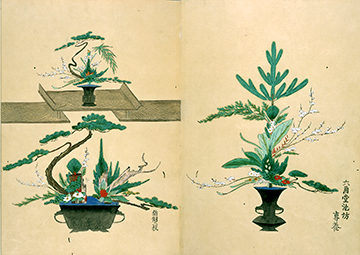

Rikka no shidai Kyujusanpei ari (Ikenobo Senko Rikka-zu) (Important Cultural Property)

This collection includes 91 drawings of rikka and sunanomono arranged between 1628 and 1635 by Senko Ikenobo II, who refined rikka. His elegant and graceful style is apparent in these works. Two drawings of rikka by other arrangers are also included.

Dissemination of Rikka and Formalization of ShokaMid-Edo period

While rikka became popular among wealthy townspeople, the need for a more simplified and dignified style of ikebana began to arise, resulting in formalization of the shoka style.

Genroku Culture and Rikka

Rikka, refined by Senko Ikenobo II, influenced the Genroku culture that flourished primarily in the Kamigata area (Kyoto and Osaka). A number of words regarding rikka appear in Joruri drama by Monzaemon Chikamatsu, suggesting rikka’s popularity among townspeople. Another characteristic of this era is that many books were published concerning ikebana. Representative of these is the “Kokon Rikka Taizen,” which provided theoretical and easily understood explanations of rikka. During Senyo Ikenobo’s era collections of rikka drawings by successive Headmasters and disciples were published, such as “Rikka-zu narabini Sunanomono” in 1673 and “Shinsen Heikazui” in 1698.

Shinsen Heikazui

Collection of 100 rikka drawings mainly by Senyo Ikenobo and his disciples, published in 1698.

Rikka for the Great Buddha at Todaiji temple

In 1692 Ikenobo disciples Sanshi Ikai and Jisui Fujikake created 9 meter-tall rikka arrangements for the ceremony marking completion of restoration of the Great Budda at Todaiji temple, Nara. At this time Ikenobo had spread throughout the country, including students from the Ryukyu Kingdom (present day Okinawa). An organizational structure of Ikenobo disciples with a leader also began to be formed.

From Nageirebana to Shoka

While creating rikka with 7 yakueda became popular, arrangements that were lighter in feeling for a small room or for the tea ceremony room began to attract interest. These arrangements were called “nageirebana.” The “Kodai Shoka Zukan,” edited by Senyo Ikenobo, shows nageirebana at this time. In the mid-18th century, Senjun Ikenobo’s era, nageirebana was formalized into a more dignified style, and this came to be called shoka.

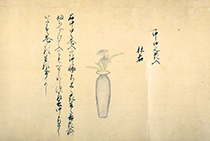

Kodai Shoka Zukan

A collection of drawings revised by Senyo Ikenobo in 1697 of arrangements that were precursors of shoka, such as nageirebana. A copy dated 1710 was handed down in Ikenobo.

Innovation in Rikka and Popularity of ShokaLate Edo Period

Senjo Ikenobo brought innovation by introducing “Mikizukuri,” methods for cutting branches and piecing them together to create ideal forms in rikka arrangements. He also established a system for passing on shoka teachings to students. Due to these achievements, the number of Ikenobo disciples reached into the tens of thousands.

Establishment of “Mikizukuri” methods

In 1797 Senjo Ikenobo published the “Shinkoku Heika Yodoshu,” the first collection in about 100 years of drawings of rikka arranged by successive Headmasters and disciples. Until then rikka had been created with ubtate methods utilizing the natural forms of trees and plants. During Senjo Ikenobo’s era mikizukuri methods for cutting branches and piecing them together to create ideal forms in rikka were introduced. In addition, the number of yakueda (main branches or parts) in rikka changed from seven to nine.

Shinkoku Heika Yodoshu

Collection of rikka drawings published in 1797. There are several similar books with the same title. The book shown in the photo includes 57 drawings edited mainly by Katei Nagata, senior disciple of Senjo Ikenobo.

Advancement of Shoka

Being a more simplified style than rikka, shoka gained much popularity during this period. Establishment of an introductory shoka course resulted in a rapid increase in the number of disciples, and Ikenobo began to include women disciples as well. Outside Kyoto the emergence of influential disciples who could be called “master” strengthened Ikenobo’s organizational structure in each prefecture. It was during this period that the passing on of traditional teachings of shoka such as “Gokajo (five teachings)” and “Shichishu (seven teachings)” was formalized, and these teachings are still carried on today. In addition to rikka, shoka began to be displayed at the traditional Tanabata gathering, establishing its position in Ikenobo.

Publication of Collections of Shoka Drawings

The 1804 “Hyakkashiki,” the first published collection of Ikenobo shoka drawings, and the “Go Hyakkashiki” of 1808 include many works by Ikenobo disciples outside Kyoto. In 1820, in response to the use of too much technique in shoka and to convey its correct form, Senjo Ikenobo published the “Soka Hyakki” collection of 100 shoka drawings.

Soka Hyakki

Collection of 100 drawings of shoka by Senjo Ikenobo. Senjo himself selected these works published in 1820. The original drawings were made by Keibun Matsumura and Seiki Yokoyama, painters of the Shijo school.

Formalization of Shoka Shofutai and Development of Nageire / MoribanaMeiji period – Early Showa Period

The Shoka shofutai style formalized by Sensho Ikenobo became popular as a style that was easy to learn and teach, and it was adopted as ikebana education. On the other hand, Nageire and Moribana styles developed as ikebana that responded to the westernization of Japanese life.

Teaching Ikebana at a women’s school

For Ikenobo, based in Kyoto and with a close relationship to the Imperial Court and warriors, the Meiji Restauration and transfer of the capital to Tokyo brought great change. To avoid decline caused by transfer of the capital, the Kyoto Expo began to be held in 1872, and Sensho Ikenobo and Ikenobo disciples participated in the exhibitions. Having been appointed as an ikebana teacher at Kyoto Prefectural Women’s School in 1879, Sensho Ikenobo focused on teaching ikebana to women. Since then the percentage of women in the ikebana population has increased rapidly. In 1889 an Ikenobo office was founded in Tokyo.

Kyugisoshoku jurokushikizufu

A set of three rikka arrangements exhibited by Sensho Ikenobo at an antiquity exhibition held in Kyoto in 1903. This exhibition is considered part of the Kyoto Expo held annually from the early Meiji period.

Establishment of Shofutai

Sensho Ikenobo established shofutai as a style that was easy to learn and to teach, and in 1904 he published “Hana no Shiori” as a textbook. This was later included in the textbook series called “Hana Kagami,” which went through several impressions. Shoan Muto traveled throughout Japan teaching on behalf of the Headmaster, and shofutai took hold and became the standard for arranging.

Nageire, Moribana and Oyobana

On the other hand nageirebana and moribana were established as ikebana that responded to westernization of lifestyles brought about by adoption of Western culture during the Meiji period. Ikenobo also adopted these styles, calling them oyobana meaning application (“oyo” in Japanese) of rikka and shoka. In 1934 Seni Ikenobo set guidelines for these styles. In 1941 Ikenobo chapters were founded throughout Japan leading to strengthening of links between Ikenobo Headquarters and local disciples.

Sensho Shokashu

A collection of shoka drawings chosen by Ikenobo Sensho himself. Even today drawings in this collection are considered as standards for Shoka shofutai.

Ikebana of TodayThe Present

After World War II, Ikenobo ikebana spread to countries around the world. The current Headmaster Sen’ei Ikenobo has introduced Shoka shimputai and subsequently Rikka shimputai, continually searching for ikebana that suits our time.

Restoration and Development after World War II

Shortly after World War II, hoping to reconstruct the nation’s culture, Ikenobo began activities such as holding ikebana exhibitions in Kyoto and Osaka. In 1952 the Ikenobo Junior College was founded with the help of disciples throughout the country. In 1968 an Ikenobo office was established in San Francisco, U.S.A., and Ikenobo’s activities in foreign countries began to gain momentum. In 1977 the Ikenobo Headquarters building was completed and the Ikenobo Central Training Institute and Ikebana History Museum were founded.

The Ikenobo Headquarters building shortly after its completion

Free Style and Shimputai

After World War II arranging styles related to nageirie and moribana began to be called jiyuka (free style), obtaining the same position in Ikenobo as styles such as rikka and shoka. In striving for styles of rikka and shoka suited to our times, the present Headmaster Sen’ei Ikenobo introduced shoka shimputai in 1977 and rikka shimputai in 1999.

-

Jiyuka (free style)

Jiyuka (free style) -

Shoka shimputai

Shoka shimputai -

Rikka shimputai

Rikka shimputai

Toward the future

On the occasion of the 550th anniversary since the name Senkei Ikenobo first appeared in historic records of the Muromachi period, the Ikenobo Ikebana 550th Year Celebration was held on a grand scale in 2012. The Ikenobo Senno Kuden of the Muromachi period is still treasured today as the most important Ikenobo teaching. Although the exhibition period has changed, the Tanabata Gathering that began in the Edo Period continues to be held today as the annual Ikenobo Tanabata Exhibition. While preserving tradition, Ikenobo will continue to pursue new ikebana.

The Headmaster Designate reproducing tatehana of the Muromachi period